- Home

- Jay Varner

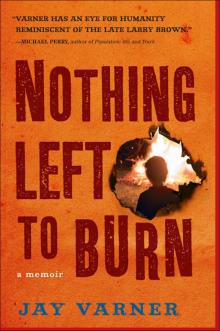

Nothing Left to Burn

Nothing Left to Burn Read online

Nothing Left to Burn

A MEMOIR | Jay Varner

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

for my father, and for his

We all live in a house on fire, no fire department to call; no way out, just the upstairs window to look out of while the fire burns the house down with us trapped, locked in it.

—Tennessee Williams, The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore

Can a man take fire in his bosom, and his clothes not be burned?

—Proverbs 6:27

Contents

Prologue

PART I

One | Two | Three | Four | Five | Six | Seven

PART II

Eight | Nine | Ten | Eleven | Twelve | Thirteen | Fourteen

PART III

Fifteen | Sixteen | Seventeen | Eighteen | Nineteen | Twenty

PART IV

Twenty-one | Twenty-two | Twenty-three | Twenty-four

Epilogue

Prologue

My grandfather Lucky drove to our trailer every Saturday morning, his silver and maroon Chevrolet pickup loaded with garbage bags piled so high they nearly spilled over the sides. Sometimes the junk was the accumulation of a week’s worth of trash from my grandparents’ apartment or the old hotel they owned. Or else the truck was full of the unwanted tires, boxes, and newspapers that Lucky offered to dispose of for his friends. I started watching Lucky’s Saturday morning ritual when I was five years old.

Each week, I parted the white curtains in our living room window and saw Lucky slowly back his truck up to the edge of a sunken pit, actually the basement of the first house my father had lived in as a child — it sat thirty yards from our trailer and was now filled with brick, cinder blocks, ragged chunks of cement, and junk too rusted to even identify. My mother and I called that spot “the hole.”

With a toothpick always plugged in his mouth, Lucky opened the door of the truck and stepped out. He was usually dressed in a white T-shirt, paint-splotched green worker’s pants, and scuffed-up leather boots, so cracked they looked as if he had just stomped the entire width of Pennsylvania. Every Saturday he walked across our yard with a hardened and dogged gait, ready to banish anything that stood in his path, and circled the crumbling cinder-block walls of yet another house my father had once lived in with his family. What was left of that building stood five yards north of our trailer and resembled ruins from a war movie.

Lucky stored his caged pigeons inside the damp walls of that second house. I hated those birds. Every time I walked past the building’s broken windows, the reveille of coos and fluttering wings spooked me and I feared the birds would somehow burst from the blackness and peck at my face, just like in the Hitchcock movie my mother never let me finish watching on television.

But Lucky loved his pigeons. One winter, he plugged lamps and space heaters into our trailer to warm them, stringing orange extension cords across our yard and inflating our electric bill. He never offered to pay his share.

“We can’t afford this,” my mother told my dad, waving the bill in front of his face. “What’s more important to you, paying to heat your father’s pigeons or keeping your family warm?”

My dad must have talked to him because Lucky removed the lamps and heaters without ever saying a word.

But the pigeons weren’t alone inside those walls. Rats inhabited the structure too. Sometimes they burrowed under our trailer only to die near the heating vents. When the furnace kicked on, the rats roasted, and the smell sifted through our kitchen and living room. After my mother once complained, Lucky set traps to catch them.

On one Saturday morning, I watched as he emerged from behind the cinder-block wall, holding a bunch of rats by their long, swinging tails. He walked back to his truck and laid the carcasses on the silver bumper.

Then, Lucky lowered the tailgate, stepped up onto the truck, and tossed the black bags of garbage into the hole. Climbing back down, he lifted a five-gallon can of gasoline from the bed and doused the junk with gasoline. When the can was nearly empty, he stepped back from the pile and poured a trail of gas for five or so feet leading from the pit. He grabbed a handful of rats off the truck, and with a flick of his wrist he swung them like lassoes and tossed them into the pit. Next, he lit a match and dropped it to the ground. Flames rose on the path he had poured and then rushed into the garbage, exploding into a wall of fire that flashed up toward the sky. The blaze wheezed a breath of air before releasing a tremendous bang, a sound as loud as my father’s hunting rifle, so thunderous that a neighbor some eighty yards away once told my mother that every Saturday morning she could hear the flare-up from inside her house.

Lucky stepped back from the fire, though he still stood so close that he could probably feel the burn of the heat inside his lungs, and pulled a white hankie from his pocket, patted his bald head, and then swabbed at the back of his hairy neck. He cocked his head like a dog, listening intently, as though the crackle and pop of the flames sounded like a melody to him. He stood with his arms crossed and stared at his fire, never moving until the last flame died out.

Part One

One

Halfway through August, a heat wave sinks into central Pennsylvania, and it feels like the countryside is sealed inside a clammy Mason jar. Sweat trickles down my back as I smoke a cigarette to calm my nerves. I have been hired as a reporter for my hometown newspaper. It’s my first night. I lean against the brown bricks outside the single-story building that houses the Sentinel and wish for a breeze or thunderstorm — anything that might funnel relief into the soupy air — but I know that none will come. The sky is mottled with haze. I toss my cigarette down into a metal coffee can, a makeshift ashtray half full of spent butts, and open the back door.

Just two days earlier I had somehow convinced Elizabeth, the newspaper’s editor, that I have the “nose for journalism” the advertisement for a reporter’s position demanded. I know how to write a story, I told her, leaving out the fact that I had taken only one journalism class in college. I told her there are the sacred five Ws — who, what, where, when, why — but beyond that, there are human stories. These are real people with real lives and I would be indebted to tell the truth. When I stood to leave, Elizabeth shook my hand and apologized about forgetting my scheduled interview; I wore a suit and tie while she stood in purple sweatpants and a T-shirt silk-screened with butterflies.

My first afternoon at the Sentinel, Elizabeth leads me through the newspaper’s small office. The low ceilings hold buzzing fluorescent lights — there seem to be no shadows cast onto the worn, brown carpet. The only natural light that seeps into the building comes from the glass facade at the front of the building. However, none of that light makes it to the newsroom because it is eclipsed by the tall, carpeted walls of cubicles that make up the advertising department.

Elizabeth introduces me to my fellow reporters, then finally shows me to my cubicle. The walls are waist high and it feels as spacious as a shoe box. Sitting on the desk is a computer that looks to be fifteen years old, perhaps a remnant from the Reagan administration. Next to the computer sits a police and fire scanner that beeps every few minutes, just like the red Motorola pager my father used to clip on his leather belt. A streak of tones, vacillating in pitch and frequency, whine from the tiny black scanner. Dread singes my nerves — I know that sound too well already.

“Why the scanner?” I ask.

“Figured we’ll start you out on police and fire,” Elizabeth says. She narrows her eyes, as if examining me. “That’ll be okay, right?”

“Sure,” I say. “Yeah, that’s no problem.”

As I stare at that scanner, I think of my father who had been McVeytown’s volunteer fire chief. Each time I pass the McVey-town Volunteer Fire Company

and see a few of the guys standing outside, I don’t swell with the pride that most people in small towns feel for their volunteer firemen — I feel the same way about them as I feel about my father. Those men abandon their families. The firehouse was my dad’s excuse to miss dinner, skip out on my elementary school’s open houses, and break plans to play baseball or take me fishing. His commitment to his job as fire chief exceeded expectations — it seemed a guttural obsession, perhaps an addiction.

My dad left home for fires, car accidents, flooded basements, company meetings, seminars, training exercises, and conventions. Even when he worked himself raw cutting glass at his factory job and complained of sore joints and bloody knuckles and stomach problems, when he was called he bolted to his feet and went out to save the day, like one of the superheroes I watched on afternoon cartoons.

He jumped from his chair at dinner, lunged out of bed in the night. He raced past cars on the highway in his pickup truck — the red strobe light on the roof flashing, the speedometer climbing, sometimes my mother and I sitting beside him and grasping the vinyl seat. One such day, he pulled into the firehouse parking lot, slamming on the brake and jerking the truck to a sudden stop. He popped the door, jumped down, and ran toward the station house.

“Just drive it home,” he yelled to my mother before he dashed into the engine room.

It was scary, amd sometimes frustrating, but there was something exciting about it as well. It was as if he kept the entire town safe, as if somehow none of us could survive without him.

My complicated history with fire seems unknown to my newsroom co-workers, many of whom are in their early thirties and probably never even heard of Denton Varner, my father. But lots of other people in Mifflin County still love him and consider him a hero. Fewer people remember, or perhaps conveniently forget, that my grandfather Lucky loved to ignite fires. I don’t say a word to Elizabeth about my family’s past, afraid that if I decline the police and fire beat, I will be fired from a job that I desperately need. Most of my friends in the class of 2003 began working jobs when we graduated three months earlier — places like insurance companies, corporate front offices, and national magazines. None of them still live in their hometown and write for their local daily newspapers.

Later that first night, I learn how to write obituaries.

Ken, the newsroom clerk, sits next to me as I type my first batch of obits. He tells me the formula on how to write up the dead. The most important things come first: name, age, address, and time and place of death. Then a new paragraph for the background: date of birth, place of birth, parents, and spouse. The next paragraph lists the survivors. There is an order to this laundry list of family members as well: The most important (usually the children) come first. Aunts, uncles, or cousins come last. The rest fall somewhere in between. There are exact rules, wordings, and euphemisms that must be followed.

Ken scratches his goatee while I type. He seems to genuinely enjoy the order of death. Faxes from the funeral homes provide the specifics of the deceased. All I have to do is arrange the information.

“We used to include the words public viewing,” Ken says. “But now it’s friends may call instead. Someone who was doing these forgot a letter once and wrote pubic instead of public. The family didn’t like that.”

“This is bitch work, isn’t it?” I ask. “The lowest job for a reporter?”

“Look at it this way,” he says, and taps a finger on the desk. “You’re guaranteed to have your stuff read. People want to know who died. They read these obituaries every day.”

When I finish for the night, I walk through the newsroom, past the tiny lunch room and the cubicles of the circulation department, and slip out the back door for a cigarette. The night looks still and haunted. A fat moon, two days past its prime, spills a blue tint over the wooded knob of a nearby hill and washes down onto the parking lot. Lightning bugs glow to life, then fade, like the flashing beacons of the radio relay towers stuck on distant ridges. In a few weeks the fireflies will disappear from the night along with the heat. It feels as if everything will go out with the summer but me.

One of the guys from the press room opens the door and steps outside for a breath of air. His blue uniform clings to the heft of his frame. Ink stains his fingers and forearms.

“We got a name for you already,” he says. “Clark Kent.”

“Well, I am wearing red underwear, but I’d need a cape.”

“No, it’s the glasses,” he says, pointing to my trendy, black-rimmed frames. “What beat do they have you working?”

“Police and fire. And writing obits.”

“I’ve seen so many people go through that desk,” he says. “I’ve just stopped learning their names. I’ve been here thirty years and let me tell you something — you’ll be gone in a year.”

“You think so?”

“I know so,” he says. “You burn out on that beat.”

I had already burned out on Mifflin County — I never even wanted to return here.

Many people in my family had not gone to college and the ones who did had attended state universities, not liberal arts schools as I had done. Though tuition had been expensive, I relied on financial aid, student loans, and grants. Most of my family worked practical jobs — they dug ditches along the railroad, reviewed loans at banks, or taught middle school. I was raised believing that college was the ultimate privilege, something sacred that should never be wasted. With that attitude, my family couldn’t understand what I would possibly pursue with a degree in creative writing. None of them had a penchant for the arts — they enjoyed things like hunting deer and turkey, fishing for trout and rock bass, or watching baseball and football. To me, moving back home was my admission of defeat, a declaration that their concerns had been justified and that my four years at college had been wasted. Here comes the prodigal son, I imagined them saying, crawling back home with his tail between his legs.

And so, on graduation day, I swallowed my pride and packed up my dorm room, loaded everything into the car, and moved back home with my mother. There was no party and no cake, just the two of us quietly watching television together that Sunday night. The place still looked exactly as I had remembered it — there was not much room, even for two people. We couldn’t even walk past each other in the hallway by turning sideways — someone had to step into the bathroom or bedrooms until the other passed. And no matter where I went — my bedroom, the corner office I had set up in the basement to write, or the front porch — I could hear every move she made. The floors squeaked and moaned as if the house were alive. I yearned for the privacy of my dorm room, which had actually been quieter.

But my mother seemed happy to have me home. We took walks together in the evenings. Once a week we mowed the lawn — she drove the riding mower, while I circled trees with the push mower. She told me things that needed to be fixed — the clothesline, a bench on the porch, the door to the shed — and I made sure they were repaired to her liking. On Sunday nights we ordered a pizza from Jimmy’s Pizza, McVeytown’s only attempt at anything resembling an Italian restaurant, and then watched baseball together.

“You know,” she said one night, “you’re going to have to get a job soon.”

“I know.”

“What were you thinking of doing?”

“Something will work out,” I said.

“When are you thinking of looking for a job?” she asked.

“I looked,” I said. “There’s not much open right now.”

“Wal-Mart’s hiring again.” She raised her eyebrows and waited for my response.

During college, I worked three summers at Wal-Mart, barely making above the minimum wage. It was bad enough then, but now that I had a degree, there was no way I would work there again.

That summer dragged on, but then I opened the newspaper and saw an advertisement for a reporting position with the Sentinel. It didn’t seem like such a bad job. Maybe it would make living in Mifflin County a bearable experience.

> The area, located almost directly between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, once thrived on agriculture and industry but now suffered in irrelevance. I had grown up in McVeytown, a blink-and-you-miss-it town that had only one store at which to buy groceries, one gas station, and two restaurants. Alfalfa and corn-fields surrounded everything; they rolled out like long tracts of green and brown carpet before meeting the undulating ridges on the horizon, part of the Appalachian Mountains’ long stretch through central Pennsylvania. At dusk, sunset fired the dairy farms in a golden hue and burnished the surface of the Juniata River. The silence of night was broken by the distant wail of a freight train as it beat and clanked along the railroad tracks, or by the machine-gunning Jake Brakes on the semis rolling on Route 522 through McVeytown.

Lewistown, the largest town in Mifflin County and home to the Sentinel office, was fifteen miles east of McVeytown and had seemed like a city when I was a kid, when I thought that I wanted to live here for the rest of my life. This was when industrial plants still clustered along the snaking Juniata River, a waterway that once transported tons of goods each day as part of the Pennsylvania Canal, back before railroad lines veined over fields and roads. Back then, factories that produced airplane parts, stereos, televisions, automobile seats, cabinets, and candy surrounded the town. Family-owned storefronts surrounded the town square.

But like so many small towns across the country, the strangle-hold of Wal-Mart spread like cancer. The stores closest to “Wally World” shut down first, then the ones on the square, and finally people had two choices: shop at Wal-Mart or don’t shop at all. Around this same time, the first of the factories began to close.

It wasn’t just the jobs that left — people did too. Since the 1960s, Lewistown’s population had decreased by 29 percent. Around twelve thousand resided in the borough in 1973. By the time I returned to Mifflin County after college, only eight thousand were left within the city limits. And though there were fewer people competing for employment openings, even dead-end jobs became increasingly difficult to find. The options for high school graduates ebbed. Grandfathers, fathers, and sons who had defined themselves by their lineage at the same manufacturing plants searched for something different to do. Their jobs went away but the old factories were left standing, mausoleums of the town’s industrial past. The buildings’ windows were boarded up; the insides stripped, boxed, and shipped overseas. Parking lots the size of football fields sat empty.

Nothing Left to Burn

Nothing Left to Burn