- Home

- Jay Varner

Nothing Left to Burn Page 20

Nothing Left to Burn Read online

Page 20

I went into Pap and Nena’s house and told them what I had seen.

“That’s illegal,” Nena said. “You can’t just bury a cow in your field.”

“What else do you do with it?” I asked.

“There’s a crew of guys who come and pick up dead animals from farms. Who knows what was wrong with it? Probably malnutrition. They can’t even take care of their cattle anymore.”

Over the next few weeks more graves appeared — a dozen or so small mounds of dirt. It was close to the end of April and the Odens had left the corn crop untouched all winter. By now, it was worthless. People in McVeytown talked about the family’s legal troubles, that the government might foreclose on the farm because Hartley owed thousands of dollars in back taxes. And now their calves were dying too.

In early May, when the days swirled with welcomed warmth, Hartley Oden drove his old Chevy Nova over the alfalfa fields and placed another machine nearly two hundred yards from my grandparents’ house. It was the size of a small television and emitted a constant whistle. He knocked at my grandparents’ door and apologized for the noise. The machine emitted sound waves that would help the crops grow, he explained. It was a new and natural procedure, he said, but the government didn’t want people to know about it. He left the machine to squeal and whistle in the field for three days.

The Odens’ farm appeared to be in complete failure. The alfalfa fields looked more like weeds than crops — Hartley’s little box machine must not have worked. But by then, the Odens hadn’t even bothered to fertilize or spray the crops with pesticides. And the stinky wagon finally broke down for good, or else it wasn’t needed — it seemed the cows had all died or had been sold. We continued to hear rumors of a sheriff’s sale.

One afternoon near the end of May, agents from the U.S. Marshall’s Office and Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, as well as Pennsylvania state troopers, surrounded the farm. The family was given one hour to gather as many belongings as possible; after that, whatever was left fell under the ownership of the Internal Revenue Service. The newspaper printed a front-page picture of the seizure. The ATF agents wore black windbreakers with the yellow lettering of their agency’s acronym sprawled across the back. They carried assault rifles. State troopers stood guard — the butts of shotguns against their hips, the barrels pointed into the sky. By that night, the farm would be vacant — the few remaining cows loaded onto cattle trucks and driven to other farms and eventually auctioned off. A state trooper would tell my grandparents to call 911 if they saw anyone from the family step foot on the farm, as they would now be trespassing on U.S. government property. In the years that followed, people still talked of Hartley Oden and his machines. Some called them witchcraft; others said he poured his money into the machines and was too broke to pay his taxes. Most everyone agreed he was crazy. The entire town wanted to pull back the rug like Ryan and I had done and see the unmistakable stains of truth.

That day of the raid, my family and I waited for the secrets of the basement to be revealed. My mother and I watched everything from the hill in my grandparents’ yard. We saw ATF agents removing the machines from the basement on dollies.

“Those must be his machines,” my mother said. “I remember when he called me once and told me that he could cure your father.”

“Would you have ever tried it?” I asked.

“Are you kidding? I wouldn’t believe a word that man said.”

In a way, I thought then that believing in Hartley Oden’s machines might be no less futile than believing in what Dr. Fawcett or Rev. Goodman had said. The new life the doctors had promised my dad beyond his bone marrow transplant didn’t happen. The understanding that Rev. Goodman had assured me did not come. Instead, I silently questioned why my father ever got cancer, why he left my mother and me alone, and why the medicine failed. But I remained a willing believer in Hartley Oden’s farm machines: though they disappeared that day of the raid, never to be seen again, at least they had never failed to deliver on their promises.

Twenty-four

Lucky died the summer after my freshman year of college. One evening, while I worked on what I believed would become my first novel, my mother stood in the doorway of my bedroom and stared at me for a moment.

“Guess what,” she said.

I looked from the computer screen and noticed something odd about her face. I couldn’t tell if she held back tears or laughter.

“Lucky died,” she said.

“Yeah. Right.”

She stared, unblinking. “No, he’s really dead.”

I looked back at the computer screen, unsure how to react. Crying seemed the proper thing, but the news struck me with great relief, as if our lives had been cured of a burning scourge. I hadn’t seen my grandfather in years — I couldn’t even remember the last time, or the last thing he had said to me. His words that day at the hospital after my dad had been diagnosed with cancer, however, did come back to me: “Hell of a thing, outliving your own son.” He had been right.

“He died this afternoon,” my mother said. “Maybe his heart just gave out.”

“What heart?” I asked.

My mother shook her head and glanced around my bedroom. “Don’t talk that way. You know your father wouldn’t want that.”

It was true. My dad never spoke a bad word about his father.

“I suppose we have to go to the funeral?”

“You know we have to,” she said. “Your father would want you to go.”

It seemed a joke. People went to funerals to pay respect, to honor the dead. I understood that I would have to attend because my father couldn’t — I had to represent him in some way. But I would have to pretend to be upset, pretend that Lucky actually meant something to me, something good and positive.

My mother continued standing in the doorway, as if waiting for something. She bit her lower lip. “There’s something I never told you about Lucky,” she said.

“He really wasn’t my grandfather?” I asked hopefully.

She smiled and said, “Come on.” She paused and then told me about a great-uncle who had worked for the telephone company in Lewistown. In the early eighties, my uncle, Nena’s brother, had been sent to repair something inside the Coleman Hotel. When he walked into the basement, he saw several full gasoline cans in the corner and a pile of oil soaked rags next to them. He deduced that my grandfather intended to burn the place down. My uncle lived in McVeytown and knew about Lucky Varner. He confronted Lucky and threatened to call the police.

“That’s true?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said.

My stomach felt like a cold knot had formed inside it. I remembered those Friday night visits to the Coleman Hotel with my father, the scores of unshaven derelicts who sweated alcohol. They lived inside that hotel; Lucky could have killed them. I imagined Lucky standing across the street from the Coleman and watching windows blow out from the heat, a hand jingling the change in his pocket, a toothpick in his mouth, and that smirk on his face. Lucky suddenly seemed even worse than I ever realized.

“Did Lucky get in trouble?” I asked. “Was he arrested?”

“I’m not sure what happened after that,” she said. “That’s all I ever found out.”

I wondered how much I didn’t know about Lucky’s life, or my father’s for that matter, and I hated that I would probably never know the entire story. All of what I knew came from my mother, or from Pap and Nena; what they knew had come from mainly secondhand sources. My mother told me that my dad rarely spoke about his childhood, the years before they met — he seemed ashamed and embarrassed. And so the questions lingered.

“How did Lucky and Helen ever buy that hotel in the first place?” I asked.

“I don’t know how they bought anything. The insurance company didn’t give them any money after that second house burned because the investigators proved it was arson.”

I looked back at my computer screen and read a few lines from my novel. If I wrote a novel about Lucky, n

one of my friends in the creative writing department at college would ever believe it — too contrived, they would say. But all of it had happened — in some inexplicable and horrific way, all of it had happened.

“You know, he was accepted back into this community,” my mother said. “He went to church, he had friends. People forgave him.”

“But they knew,” I said. “They knew what he had done. All they had to do was drive here and look at those two houses, that workshop.”

How could McVeytown forgive or forget Lucky’s crimes? Many in town still ignored my mother when they saw her. They still resented her for not having a fireman’s funeral for my father, and that had been ten years earlier. It seemed absurd. It felt unfair. But at least Lucky would never strike another match. I looked up at my mother and smiled, almost laughing.

She narrowed her eyes. “What?”

“I hope it’s hot enough for him,” I said. I stomped my foot a few times and looked at the floor. “You like the flames down there?”

My mother pursed her lips and turned, walking down the hallway toward the kitchen.

“Think they’ll cremate him? A little fire for old times’ sake,” I said.

• • •

Lucky wore a suit in his casket. Even in death, he still had that same smirk, as if somehow he had gotten the last laugh. Both of my uncles eulogized their father. They spoke about his nickname — his birth certificate read Simon Varner, though everyone knew him as Lucky. It seemed fitting, both of them said, because Lucky had indeed been lucky throughout his life — he prospered as a carpenter, had three sons and a loving wife.

I elbowed my mother and rolled my eyes.

Helen sobbed throughout the service. Her shoulders were now hunched and her sons had to help her walk. At the end of the service, they led her to the casket. She wept and cried out, “Oh Lucky.” She crumbled to the ground and wailed.

My mother and I walked away from the church as if escaping from jail. I couldn’t leave the family behind fast enough.

“What a sad old woman,” I said. “She deserves this. She deserves to sit alone, without Lucky, and think about what she did.”

“Do you have to talk like that?” my mother said. “I know they’re terrible, but she loved him.”

“But she’s no better than him. What she did to Dad? She pushed him into the fire company.”

“Yes she did,” my mother said. “I know.”

Helen almost seemed like my father’s Lady Macbeth, full of direst cruelty and ready to push her son into the fire company for the sake of her and Lucky. Their damned spots sat in our yard still, the remnants of the house and the garage. What was done could not be undone.

I turned to my mother. “What if Dad hadn’t gone to all those fires? What if he hadn’t breathed all that smoke? Maybe he’d still be here. All of it’s as much her fault as it is Lucky’s. She led him toward the firehouse. She loved what he did because it made her look good and it made Lucky look good.” I stopped, panting for breath. My heart raced. I swallowed and laughed, hoping to calm my rant.

“You’re supposed to forgive people,” my mother said.

“I can’t forgive them,” I said. “I won’t.”

Not long after Lucky died, Helen sold their home outside McVeytown and moved into a nursing home. My uncles, Curt and Russ, cleared the furniture out of the house and boxed dishes and books. One Saturday morning, they called me and said that they had a box of things that had belonged to my father. They had almost thrown the box away, but then they wondered if I might want it. So I drove to that house and talked to my uncles. They were both older now, with graying hair and paunchy stomachs, and neither looked much like my father. They asked me the usual questions about my college major and my interests. When I told them that I played guitar, they both smiled.

“Your dad would have loved that,” Russ said. “The three of us used to play together every weekend. Man, those were fun times.”

“Your dad could tear through ‘Pipeline’ on his electric guitar,” Curt said.

We looked at each other for a few moments, searching for something else to talk about. Aside from blood, we shared very little. I wondered how often they still thought of my father, or about Lucky’s fires. Finally, Russ handed me a heavy cardboard box. I thanked them both for calling me.

That night, the first things I found inside the box were some of my old school pictures from elementary and middle school — even after my dad died, I still gave one to Helen and Lucky each year. The photos were folded and ripped, as if they had been carelessly thrown into a kitchen drawer.

Next, I found a letter dated November 1, 1978, from one of my father’s friends, who had lived in Texas, a man named Carl Garver. He had addressed it to Lewistown, where my dad lived with his parents. I read the letter aloud to my mother — she vaguely remembered my father talking about a Carl who had moved to Texas to become a state trooper. He wrote to my father about longing for the “Varner-Garver talks” about what was “really happening” in Mifflin County. It reminded me of the talks my cousin Trevor and I had about our hometown.

“You know what, Dent?” Carl wrote. “I never really grew up with the idea of leaving home as soon as I did but things kind of happen and all of a sudden one finds himself looking in a mirror and reflecting back on how quickly everything happens. I never appreciated McVeytown and its people as much as I did when I left.”

He signed the letter “Goober.”

The friendship between Goober and my father expressed in the letter left me with an empty feeling. I still missed him. Adolescence was long behind me, the time when parents always seemed at odds with their children. If he were still alive, it felt like we would have been good friends.

I continued sifting through the box, digging deep into my father’s late teenage years. I read the program for my father’s Eagle Scout ceremony, held on January 29, 1973 — he would have been seventeen then. In the brief biography printed inside, I learned that my dad had played soccer, was a member of McVeytown United Methodist Church, was a junior fireman, and was already in training to become an ambulance attendant. Among the merit badges he had earned in Boy Scouts were lifesaving, safety, first aid, and firemanship.

The next year, my father graduated from Rothrock High School — the program, dated June 3, 1974, included the names of his sixty-two classmates. I also read his report cards — most of his classes senior year focused on industrial arts such as mechanical drawing and drafting. He carried a B – average throughout high school.

Not surprisingly, many of the things in the box shed light on my father’s burgeoning obsession with fire.

There were the notes he kept about firefighting, incredibly a four-page outline of how to prevent and fight fires. The papers weren’t dated, but I assumed it had been work for his Boy Scouts’ firemanship badge.

“Heat, fuel, and air are the only objects needed for fire,” he wrote. “Without air, a fire would suffocate. Without fuel, a fire would have nothing to burn.” He listed the five principal causes of fire: heating equipment, careless smoking, faulty wiring, mishandling flammable liquids, and children playing with matches. “Keep matches out of reach of children,” he warned.

Below this, he drew a map of his house — the second one that Lucky had burned — and labeled the bedrooms for his parents and brothers. He pledged that if “a small fire should start” in the house, he would attempt to control the flames until the fire department arrived.

The pages of notes ended abruptly with another cause of fire: “Arson — police investigation.” After that, his scoutmaster wrote a note that said my dad knew “how to clear an area and start a fire and also how to put a fire out and leave the area in better condition than when he first went there.” I reread those words, amazed at their premonition — my dad placed the doublewide on the foundation of one of the houses Lucky had burned.

As I looked closer at that piece of paper, I noticed the left edge looked brown, almost singed. I found a sma

ll pamphlet published by the Boy Scouts of America titled “Firemanship.” The paper cover looked brown as well, as if it had been placed near heat. Then I realized that they had survived that second fire — my grandfather’s flames had licked my father’s notes, the pamphlet. My father’s Bible had even been burned — I found it in a plastic bag, coverless and with the first several pages burned off. This is something to pass on to a child, I thought.

I read birthday cards friends had sent him, letters and bulletins from the Boy Scouts, newspaper clippings of his high school classmates, and Valentine’s Day cards my mother had given him. At the bottom of the box, I found an anonymously written poem that had been read at his Eagle Scout ceremony. I never discovered who chose this poem for the ceremony or why, but I believed the words held special relevance to my father. I imagined reading it through his eyes and thinking about all that Lucky had destroyed in their lives.

TEARING DOWN OR BUILDING UP

I watched them tearing a building down,

A gang of men in a busy town.

With a ho-heave-ho and a lusty yell

They swung a beam and the side wall fell.

I asked the foreman, “Are these men skilled,

And the men you’d hire if you had to build?”

He gave a laugh and said: “No indeed!

Just common labor is all I need.

I can easily wreck in a day or two

What builders have taken a year to do.”

And I thought to myself as I went away,

Which of these roles have I tried to play?

Am I a builder who works with care,

Measuring life by the rule and square,

Am I shaping my deeds to a well-made plan,

Or am I a wrecker, who walks the town

Content with the labor of tearing down?

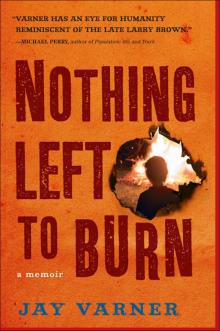

Nothing Left to Burn

Nothing Left to Burn